by Margaret Weinberg

We are excited to announce and share a four-part series of oral histories that were made possible through a community grant from the Alabama Bicentennial Commission. One story of Red Mountain mining and camp life will be released weekly through our website and social media. Our bicentennial project will culminate on July 10th with the addition of new destinations on our TravelstorysGPS app and the unveiling of a new interpretive sign memorializing the contributions of Ervin Batain, former Red Mountain Park Commissioner and founder of 3D at No. 11 Mining Camp and Nature Trail.

Today we continue with Jack Neal…

A US Steel Family

Jack Neal’s connections at US Steel go beyond his birth at the Lloyd Nolan Hospital in Fairfield, a Tennessee Coal and Iron-run facility established as “Employees Hospital” in 1949. Jack’s father, also George M. Neal, was a superintendent at the Wenonah mines. His maternal grandfather, George B. Neal, Jr. was also a superintendent, at the Dolonah Quarry, and his maternal grandfather, Clyde Neville Garmon, was a company doctor at the dispensary in Fairfield.

Even Jack’s great-grandfather, George B. Neal, Sr. worked for the mines — for the Woodward company, TCI’s predecessor. Jack, his parents and sister, and both pairs of his grandparents all lived in Wenonah, a mining community, within five miles of each other. He fondly remembers their neighborhood as the “street with curbs,” one of the only in Wenonah and a privilege that came with his father’s superintendent position. Jack Neal recently donated a number of artifacts to Red Mountain Park and we brought him up to Mine No.10 to learn a little bit more about these objects and his early life in Wenonah.

A Wenonah Childhood

Jack Neal remembers the communities around Red Mountain feeling rural. His grandparents raised chickens and kept orchards and gardens, the sound of the hens occasionally driving his mother crazy. As a young child Jack often went with his father or grandfathers on the job to the mines, the Dolonah Quarry or the dispensary. He describes the experience of being at the mines as a young boy, and hearing the steam whistle that he donated to Red Mountain.

Jack Neal, 4.29.19 00:06:20 – 00:08:26 and 00:24:47 – 00:25:47: Let’s see, my father would come home from work and you know when he was, I couldn’t tell you what time – it was in the afternoon, whatever time it was. But it was time enough that there was daylight and he would get me and take me to the top of the tipple here, I don’t think it was this mine, but the part up there at the end where the car came out of the mine and we would stand there and there was a series of bells and noises that would take place when they were ready to remove a car of ore out of the hole. And you would hear, there was cable, I don’t know if you – this is in the view or not, but there’s a weighted cable here at my feet that’s all rusted. Back in those days they weren’t rusted, they were shiny silver. It stretched from the wheelhouse all the way down into the mine. And I guess there were maybe two cables. But anyway that – the right whistle or buzzer or bell would say and that wheel would start turning and the slack would come out of that cable and it would slowly start moving. And after a while it would be moving faster and faster and faster. And then you start feeling the ground shake. Then you start hearing rumbling. And by the time that car burst out of the – into view – this cable, I guess it was slapping the ties of the track. I don’t know what made it, but it was literally signing. It was going so fast. And the car would (noise) come out and in my mind’s eye I seem to think there was something that tripped it would make it turn and dump into – I don’t know if it was going to crushers or rail cars or where it was going, but I just can’t remember that detail, but I remember the cacophony of noise. (transition) Well this is a steam whistle that has came into my father’s possession – well, I’m given to understand that it is the steam whistle that was mounted on the Wenonah – I think I’m correct in saying this – powerhouse, where the blowers and you know, big industrial type stuff like that was. And it would be blown on shift changes, on other emergencies and other occasions that I’m really not privy to, but I can vividly remember one of the highlights of my life was hearing this whistle blow. And if you’ve never heard a steam whistle that large blow with full power, it’s an experience not to be forgotten.

Jack Neal’s father, George M. Neal, remembered that whistle as well. In an oral history with Samford University in 1982 he recalls the use of the whistle to announce the beginning of new shifts, and their silence during the Great Depression when little work was available. He recalls the joy felt as a teenager at hearing the whistles blow for the first time in months, and the celebration amongst those living in Wenonah.

Jack donated two additional artifacts to Red Mountain, which he describes to us here — one of which, the sterling silver loving cup, was found by a family friend in an antique store in Chicago.

Jack Neal, 4.29.19 00:27:17 – 00:28:38 AND 00:36:25 – 00:37:51: Well, this, as it says is a portionalized sign: “Safety First” which was the mantra of the US Steel corporation. It says mine bell signals. And I would, I’m told, I never saw one of these when it was mounted on a mine, but again my father saved it from the scrap heap and it’s got all the signals and bell information and instructions of how you properly operated safety safely in a mine, in this area. And there was a series of bells and rings and so I did hear the bells ring, I didn’t really know they had a code that they were going by. But it will tell you like, two rings are hoist, three rings are hoist slowly, four lower slowly. I – when I read this recently when I was bringing it out or getting it ready to bring to y’all I read two rings hoist, three rings hoist slowly, so the there is when you hear two rings don’t rush to hoist, you might hear a third one, you know, I thought those were a little backwards maybe. (transition) I’m told that TCI and US Steel had a very sophisticated educational system. They had a black school, now back when we were talking about segregation, they did have the colored schools, as they called them, and the white schools, in each of the camps – Muscoda, Delonah, Wenonah, there’s another one, but each of them had a school, and they had a real corporate board of education that worked really hard to educate the students. And they had these sterling loving cups. This is the – it says Tennessee, Coal, Iron and Railroad Company – which should give you some idea of its age, because that’s pre-merger with US Steel or acquisition – Department of Social Science for General Excellence Award and then its lists (listing… Docena Colored, etc) – and then it stops in 1933.

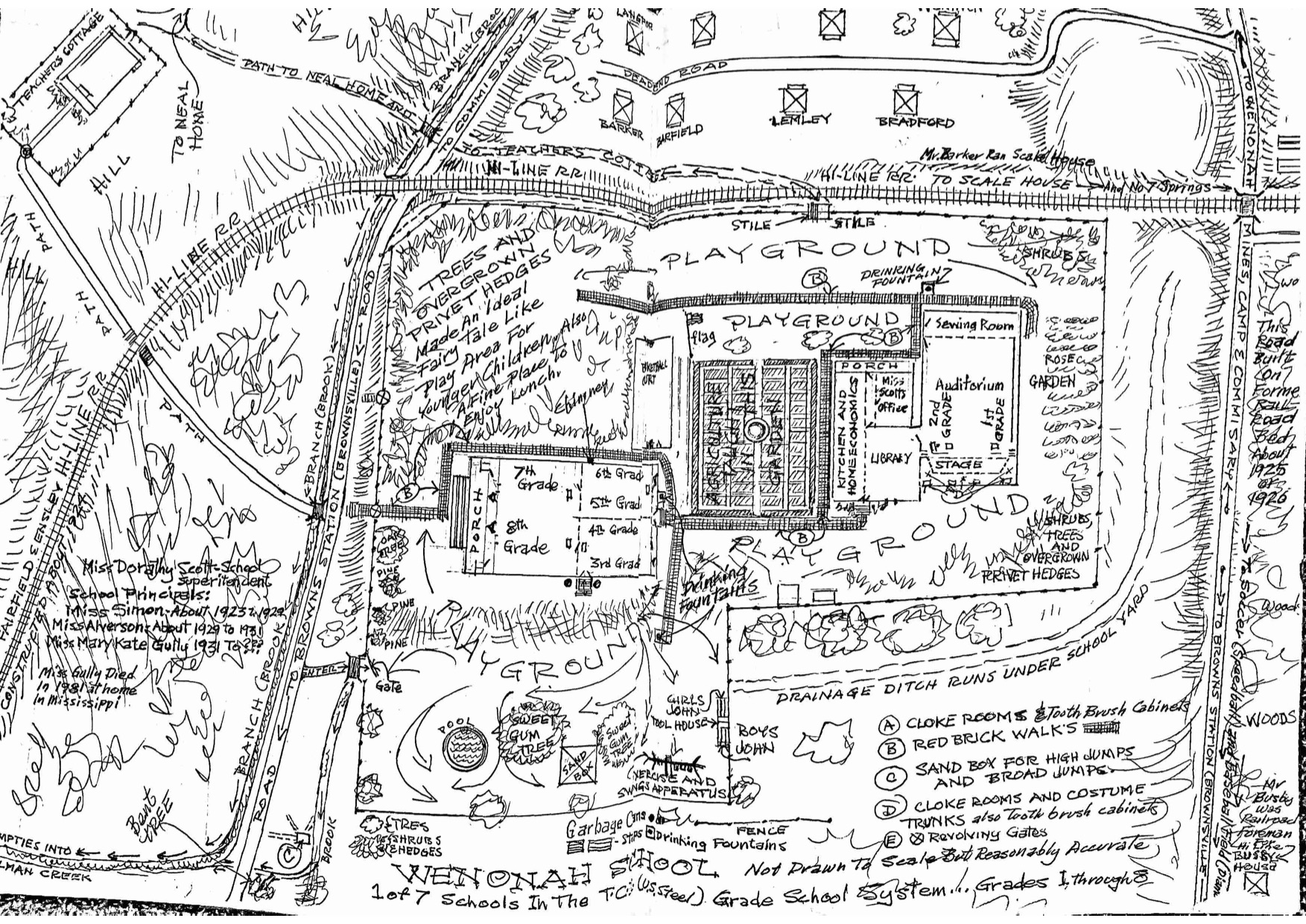

Mr. Neal also gave us this image of the Wenonah School, drawn from memory by the same Mr. Ben Wyatt who gave his parents the sterling silver loving cup discussed above.

The End of the “Company Town”

1933 was the year in which TCI turned its schools over the county and stopped employing teachers and social workers in the mining camps. Jack Neal, who lived in Wenonah in the late 1940s and early 1950s, never attended one of the company schools, his family moving out of the community at the age of five. In his young life he experienced the tail end of the “company town” as discussed here and in our feature on Mrs. Juanita Hixon [hyperlink]. In 1952, US Steel sold 3,000 units of company housing across the eight villages of Muscoda, Wenonah, Ishkooda, Dolonah, Wylam, Docena, Edgewater and Bayview, giving employees options to buy their homes.

Jack Neal became one of the first in his family to not go work for US Steel. In fact he remembers there being very little discussion of him going to work for the company. After leaving Wenonah, his family returned every Sunday to see his grandparents, until the 1960s when the mines closed and his remaining grandmother relocated to West End, where his family lived at the time. Jack Neal attended University of Alabama and become a lawyer in Birmingham, where he still lives today. As we ended our conversation at Mine No.10 he reflected on his start in Wenonah.

Jack Neal, 4.29.19: 00:39:30 – 04:24: I will say that in this day and age there’s sort of a mindset that if you – you gotta grow up in a certain place, gotta to go to school in a certain place, da-di-da-da, and it’s enriching to look back at just see what became of some of the guttersnipes that we all were and lived with in Wenonah. I say that very affectionately.

Additional Resources

“Lloyd Nolan.” Encyclopedia of Alabama.

Longnecker White, Marjorie. The Birmingham District: An Industrial History and Guide. Birmingham Historical Society, 1998.