In 1819

While Alabama was achieving statehood, native hunters and travelers encountered a fine dust that stained all with which it came into contact a distinctive red color.

The powdery dust was the residue of hematite—the word derived from the Greek for “blood,” haima—a type of iron ore which, unknown to the native population, lay in rich veins beneath the mountain’s surface. The Creeks, in particular, found a variety of practical uses for the red dust, using it to dye clothing, decorate pottery and paint their bodies for ceremony and battle.

The area would remain a network of small farming communities for more than a half-century, and for much of that time, the new settlers of Jefferson County knew little more than the native population had about how to exploit the vast seams of iron ore in what had become known as Red Mountain. By the 1840s, however, a pioneer farmer named Baylis Earle Grace—probably the first person in the area to identify the red rock as hematite—began to strip the ore from his land and send it to a forge in nearby Bibb County to be smelted for use by local blacksmiths.

During the two decades prior to the Civil War, others recognized the economic potential of Red Mountain ore. As war became imminent, speculators bought up large tracts of land in Jefferson County, aiming to supply iron for making armaments and meeting other needs of the Confederate army. Frank Gilmer and John T. Milner founded the Oxmoor Furnaces and opened Red Mountain’s first commercial ore mine in late 1863.

This mine became known as Eureka 1 and is located on Red Mountain Park. In 1864, Wallace McElwain built the Irondale Furnace (Cahaba Iron Works) and supplied it with iron ore via tramway from the nearby Helen Bess mine. Union troops, led by General James H. Wilson, destroyed both furnaces as they swept through Alabama late in the war. These early furnaces laid the foundation for future growth and prosperity. Soon enough, the “secret” of Red Mountain would be a secret no more.

Iron and steel remained the unrivaled linchpin of the local economy—a reliance upon a single industrial sector that came to haunt Birmingham with the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. Hard times came to Birmingham earlier, and left it later, than in virtually any other city. President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration was moved to refer to Birmingham as “the worst-hit town in the country.”

While the sheer amount of iron ore in the ground was impressive, those reserves were only one of a trio of natural resources that made the area unique. Along with the ore, Jefferson County and the surrounding region also had tremendous quantities of limestone and coal. When Birmingham was founded in 1871, it was envisioned by its founders as the first industrial city and the hope of the “New South”. It was rightly touted as the only place in the world where all of the raw ingredients of iron could be found in such close proximity.

Early threats to its existence, such as a cholera epidemic and concurrent national financial panic in 1873, nearly wiped out the fledgling city. Experiments at Oxmoor Furnace in 1876 proved that local coal could be made into coke for blast furnace fuel. Birmingham was now free from the limits of charcoal-fueled furnaces. The town rebounded in the 1880s, earning itself the nickname “The Magic City.” The population of Jefferson County surged from a total of 11,000 people in 1860 to more than 140,000 by 1900. By that time, iron and steel manufacturing was firmly established as the engine of the local economy. More than any other city of the time, Birmingham had become an “overnight” success story, with Red Mountain the primary source of its prosperity and prominence.

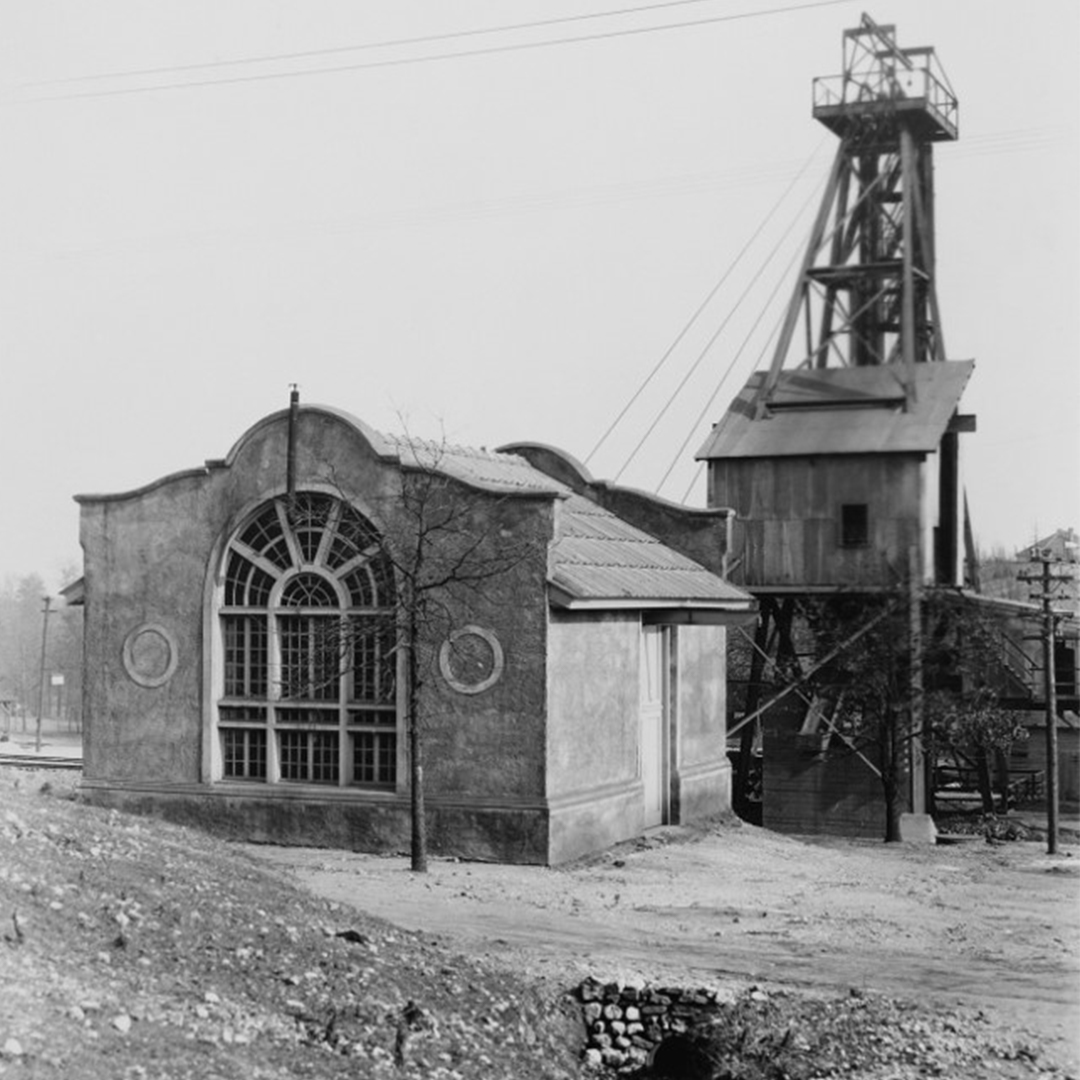

Red Mountain developed at steadfast pace. Pioneer industrialists such as Henry F. DeBardeleben, James W. Sloss, and T.T. Hillman ushered in an explosion of ore mining activity to support Birmingham blast furnace operations as they developed. Jones Valley’s first blast furnace, Alice, was partly supplied with iron ore from the Redding mines that will be an extensively developed part of Red Mountain Park. Iron ore flowed from the new mines over freshly laid rail of the Alabama Great Southern Railroad, and later via the Louisville & Nashville’s (L&N) Birmingham Mineral Railroad that first reached the Redding area in 1884.

A major change in Birmingham’s corporate landscape came in 1907, when United States Steel acquired Birmingham’s largest manufacturer, the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company (TCI). After the arrival of U.S. Steel, boom times continued in Birmingham for another two decades. By 1920, the city alone boasted a population of nearly 180,000, making it the fourth-largest Southern city, behind New Orleans, Louisville and Atlanta.

Through various programs of Roosevelt’s New Deal, the federal government spent millions toward relieving the Depression’s effects in Birmingham throughout the 1930s. Significant relief did not come, however, until the onset of World War II created new demand for iron and steel.

The war put Birmingham and Red Mountain back to work, as the city earned a new nickname: the Arsenal of the South. Factories that had been slowed or idled for a decade now helped power America’s war effort, producing airplanes, artillery shells, bomb casings, rocket bodies and steel for cargo ships. All told, Birmingham accounted for more than three-quarters of all war materials produced by the U.S. Government’s Southeastern Ordnance District.

After the war, Birmingham remained one of the nation’s leading iron and steel centers, but change was on the way. Changes in manufacturing, difficulty in accessing ore seams, and increased foreign importing contributed to the decline of what had been Birmingham’s lifeblood since its founding. The last active ore mine on Red Mountain Park property closed in 1962. Much of the land that comprised the company’s former mining sites remained untouched for almost 50 years. But in 2007, through the efforts of the Freshwater Land Trust and through the ideas of Park neighbor Ervin Battain and a dedicated steering committee, U.S. Steel made one of the largest corporate land donations in the nation’s history, selling more than 1,200 acres at a tremendously discounted price to the Red Mountain Park and Recreational Area Commission. That transaction made possible the creation of Red Mountain Park, the opening of which makes Birmingham one of the “greenest” cities in America in terms of public park space per resident.

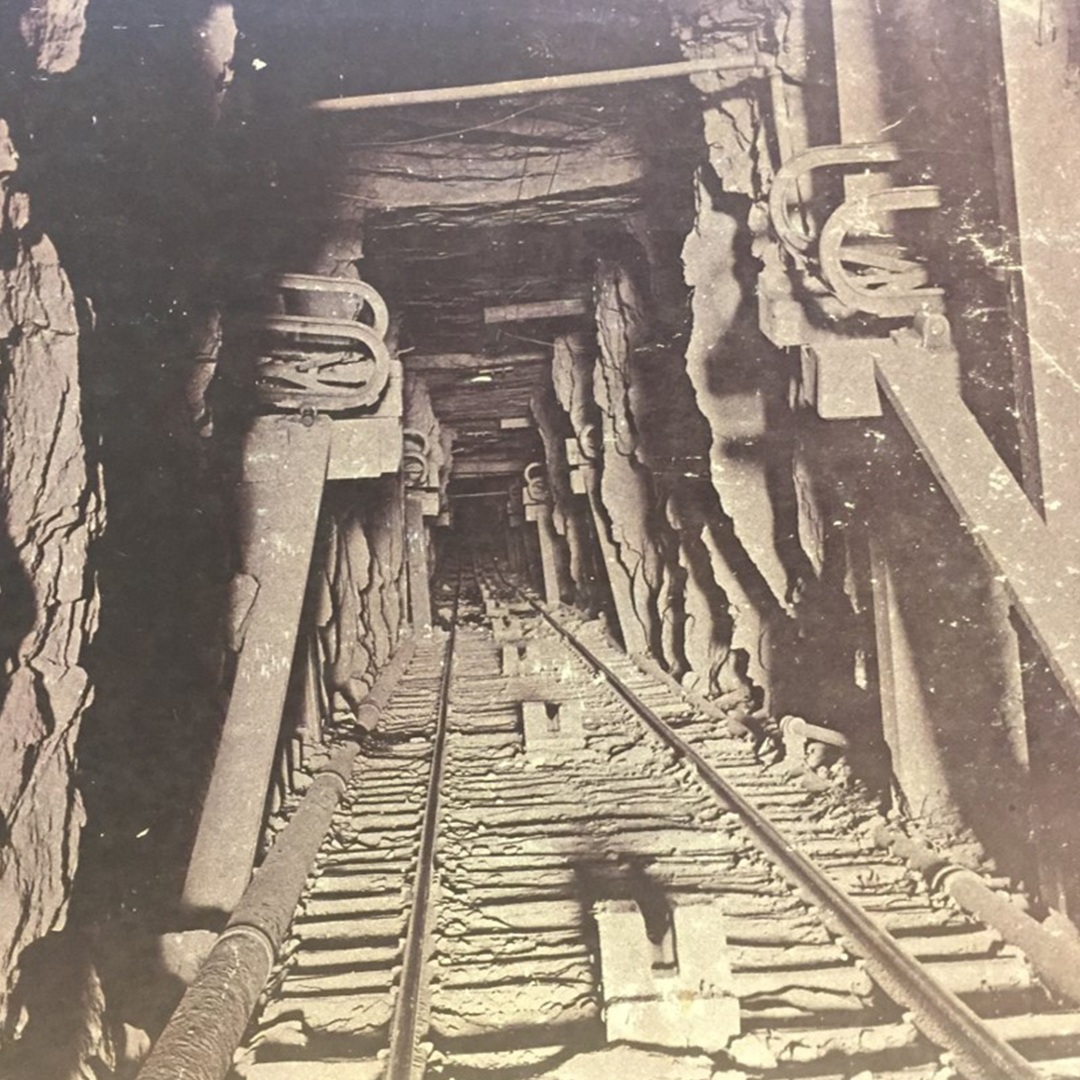

The last active ore mine on Red Mountain Park property closed in 1962 and remained untouched for nearly 50 years until the development of Red Mountain Park. The Park is covered with the remnants and artifacts of a remarkable mining history that can be seen along most of our trails and attractions.

The Oral History Project

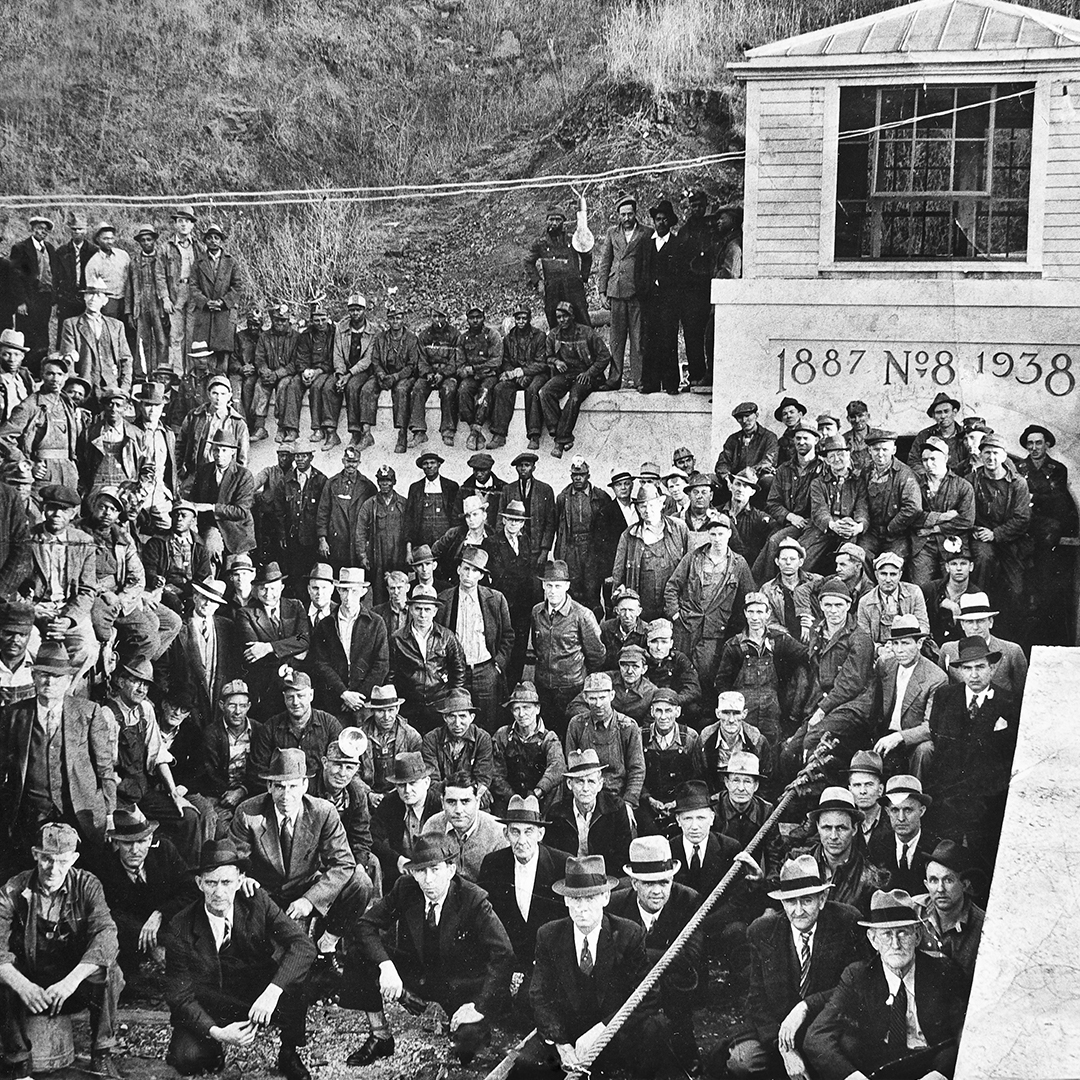

Among the primary goals of Red Mountain Park is to honor the significant contributions to Birmingham’s economic and cultural development made by iron and steel workers, their families, and the communities in which they lived.

One means of accomplishing this is through the collection and presentation of oral histories. Begun in 2009, the Red Mountain Park Oral History Project will be an ongoing effort to preserve, enrich and perpetuate the historical record of Birmingham and Red Mountain. The project is a collaborative effort with Rosie O’Beirne and the Digital Studies Department at the University of Alabama Birmingham and Birmingham-based photographer Melissa Springer, who has provided still photography for the project.

If you have a personal connection to mining on Red Mountain and a story to tell about it—or if you know someone who does—please contact us to arrange an interview.